Moving from 'AI-assisted' to 'AI-native' isn't just about speed—it changes the fundamental physics of how software is built, managed, and scaled.

Summary

Most engineering teams today are 'AI-assisted,' using tools like Copilot to autocomplete syntax while retaining traditional workflows. However, a radical shift occurs when adoption hits 100%—when no code is written by hand. This article explores the emerging playbook of the 'AI-native' organization, where the unit of labor shifts to a 1:1 ratio of engineers to products. We dissect the concept of Compounding Engineering—a process where every feature built updates the AI's context to make the next feature easier—and examine the second-order effects on organizational physics, from 'fractured attention' productivity to the collapse of traditional onboarding costs. Finally, we weigh the immense leverage of this model against the rising risks of 'digital pollution' and the erosion of deep technical expertise.

Key Takeaways; TLDR;

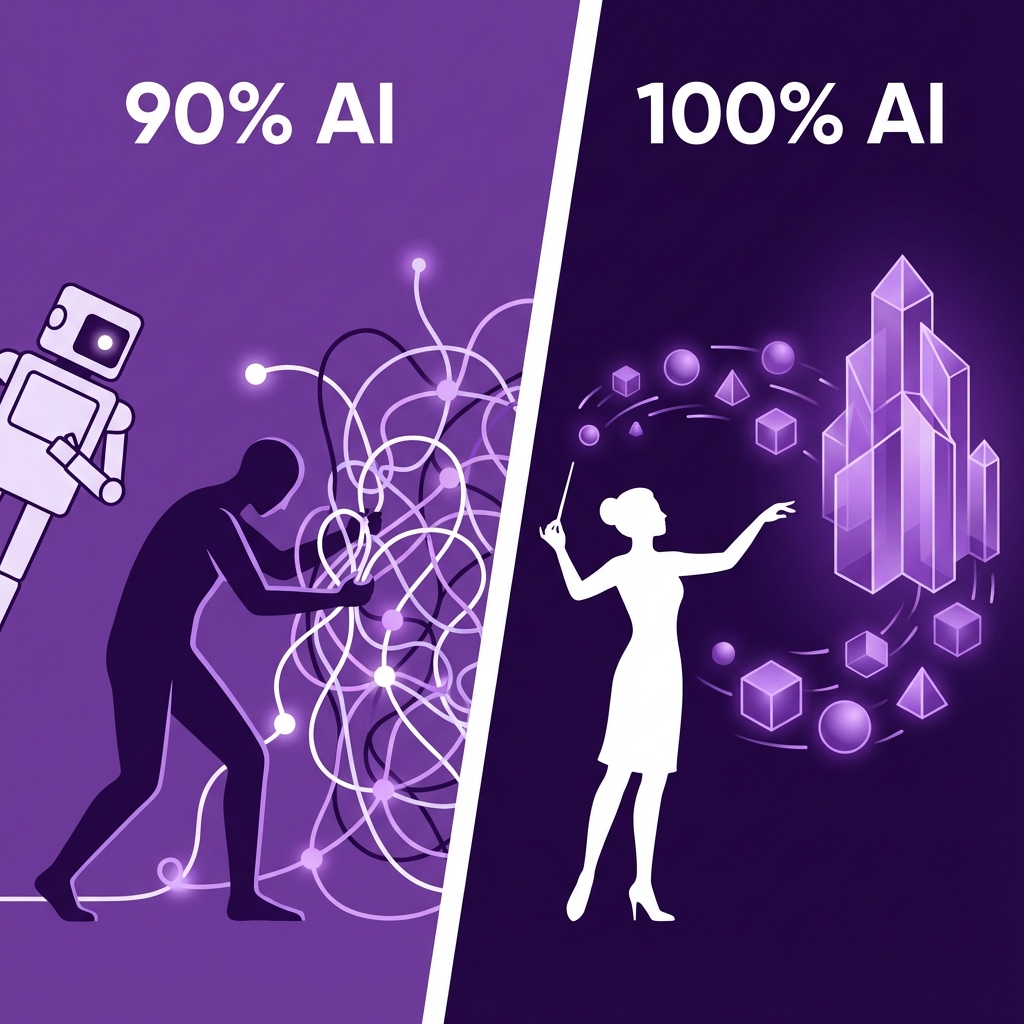

- The 90% vs. 100% Gap: Partial AI adoption retains the friction of manual coding; 100% adoption creates a phase change where the primary interface becomes natural language, not syntax.

- Compounding Engineering: A new loop (Plan → Delegate → Assess → Codify) where the 'Codify' step turns tacit knowledge into persistent prompts, reversing the traditional accumulation of technical debt.

- The 1:1 Ratio: AI-native teams can sustain complex production apps with a single engineer, fundamentally altering startup economics.

- Fractured Attention: Because agents hold context, engineers (and managers) can contribute meaningful code in 15-minute bursts, eliminating the need for long blocks of 'deep work'.

- Tacit Code Sharing: Instead of abstracting shared logic into rigid libraries, agents can simply 'read' other repositories to replicate patterns, creating a fluid form of code reuse.

- The Risk of Bloat: Without strict 'codification' of constraints, AI-native codebases risk becoming unmaintainable 'digital pollution' at a speed humans cannot manage. There is a deceptive smoothness to the current adoption of AI in software engineering. Most teams today are "AI-assisted." They use GitHub Copilot to autocomplete boilerplate or ChatGPT to explain obscure error messages. They are faster, certainly—studies suggest productivity gains of 20–50% —but their fundamental process remains unchanged. They still think in syntax, they still manually manage context, and they still view the code editor as their primary canvas.

But a different reality emerges when you push that adoption from 90% to 100%. When an engineering team stops writing code by hand entirely—delegating all implementation to agents—the organization undergoes a phase change. It is not merely a linear increase in speed; it is a shift in the state of matter of software development.

In this new "AI-native" state, the constraints that have defined engineering management for decades—the high cost of context switching, the difficulty of onboarding, and the accumulation of technical debt—begin to dissolve, replaced by new physics and new risks.

The Phase Change: 90% vs. 100%

The difference between a team that mostly uses AI and one that only uses AI is the difference between a hybrid car and an electric vehicle. The hybrid still needs a transmission, a gas tank, and an exhaust system. It carries the legacy complexity of the internal combustion engine. Similarly, the "AI-assisted" engineer still carries the cognitive load of syntax. They must mentally parse the loop structure, the variable types, and the import statements.

The Friction Gap: Partial adoption leaves the engineer entangled in syntax. Full adoption elevates them to orchestration.

When you move to 100% adoption, the primary interface shifts from the Integrated Development Environment (IDE) to the natural language prompt. The engineer stops being a writer of code and becomes an architect of intent. This shift eliminates the "friction of syntax"—the mental energy spent translating a concept into a specific language's grammar.

In this environment, the organization can abandon the defensive crouch that characterizes modern software engineering. We no longer need to fear large refactors or experimental prototypes because the cost of generating code has collapsed to near zero. The constraint shifts from "how long will this take to type and debug?" to "how clearly can I articulate what I want?"

The New Unit of Labor: One Engineer, One Product

For the last twenty years, the industry standard for a "pizza team" (the smallest unit of software delivery) has been 5–8 people: a product manager, a designer, and several engineers. In the AI-native model, this ratio collapses. We are seeing the emergence of the 1:1 ratio: one engineer, one complex production product.

Consider the case of Every, a media and software company that runs four distinct, complex SaaS products with a team of just 15 people total . Each application—ranging from an AI email assistant to a speech-to-text tool—is built and maintained by a single developer. These are not toys; they are revenue-generating products with thousands of users.

This efficiency is possible because the AI agent acts as a force multiplier, effectively staffing the "team" with infinite junior developers who work in parallel. A single human engineer can open four terminal windows, dispatch four agents to work on four different features or bugs, and then review their work. The human becomes the bottleneck only in decision-making, not in execution.

The Framework: Compounding Engineering

In traditional software development, entropy is the enemy. As a codebase grows, it becomes complex and unwieldy. Each new feature is harder to build than the last because it must navigate an ever-thickening web of existing logic. This is the law of diminishing returns in engineering.

The AI-native model introduces a counter-force: Compounding Engineering. The goal of compounding engineering is to ensure that each feature makes the next feature easier to build.

This is achieved through a four-step loop:

- Plan: The engineer writes a detailed natural language spec.

- Delegate: The agent executes the plan, writing code and tests.

- Assess: The engineer reviews the output (via tests, visual inspection, or agent-based review).

- Codify: This is the critical step. The engineer takes the learnings—the edge cases missed, the specific patterns preferred, the architectural decisions made—and writes them back into the system's context (e.g., a

CLAUDE.mdor system prompt file).

The Compounding Loop: The 'Codify' step is the engine of improvement, turning every bug fix into a permanent instruction for the future.

In a traditional team, "learning" is stored in the brains of senior engineers. If they leave, the knowledge leaves. In an AI-native team, learning is stored in the context files. When an agent makes a mistake (e.g., using the wrong date library), the engineer doesn't just fix the code; they update the context file to say, "Always use date-fns for time manipulation."

The next time an agent touches the code, it "knows" this rule. The codebase becomes self-documenting and self-reinforcing. The "senior engineer" is effectively the prompt library, which never sleeps and never quits.

The Death of the Library and the Rise of Pattern Portability

One of the most fascinating second-order effects of this shift is the change in how code is shared. Historically, if two products needed the same functionality (say, a specific OAuth flow), engineers would abstract that code into a shared library. This is "good engineering," but it introduces coupling and maintenance overhead.

In an AI-native environment, we see the rise of Tacit Code Sharing. Because agents can read and analyze code at superhuman speeds, an engineer working on Product A can simply point their agent at Product B's repository and say, "Implement authentication like they did over there."

The agent reads the other repo, understands the pattern, and re-implements it in the context of the new product. It adapts the code to the local tech stack and conventions. We get the benefit of reuse without the burden of a shared dependency. It is "copy-paste" engineering, but intelligent and adaptive—a practice that would be heresy in a traditional shop but is a superpower in an AI-native one.

Organizational Physics: Fractured Attention and the Manager-Coder

Perhaps the most counter-intuitive shift is the return of the "Manager-Coder."

Paul Graham famously distinguished between the "Maker's Schedule" (long, uninterrupted blocks of time) and the "Manager's Schedule" (fragmented 30-minute slots) . Traditional coding requires the Maker's Schedule because loading the context of a complex system into the human brain takes time. If you are interrupted, that mental house of cards collapses.

AI agents invert this requirement. The agent holds the context. It remembers the file structure, the variable names, and the plan.

This allows for Fractured Attention Productivity. A manager or CEO can step out of a meeting, spend 15 minutes reviewing a plan or dispatching an agent to fix a bug, and then switch tasks again. When they return, the agent has completed the work or is waiting for review. The "loading time" for the human is drastically reduced because the agent presents a summarized diff or a specific question.

This means technical leadership can stay hands-on. They can fix "paper cuts"—small, annoying bugs that usually get deprioritized—without derailing the roadmap. It creates a culture where everyone, regardless of title, can contribute to the product.

The Risks: Digital Pollution and the Black Box

It would be intellectually dishonest to present this shift without acknowledging the profound risks. The "100% AI" model is not a free lunch; it trades one set of problems for another.

1. Digital Pollution

When code is cheap to produce, we risk producing too much of it. AI agents can easily generate bloated, verbose, or redundant code . Without the "Codify" step rigorously enforcing simplicity and constraints, a codebase can quickly become a sprawling mess of "digital pollution"—working code that is impossible for a human to understand or debug when the AI inevitably fails.

2. The Junior Developer Problem

If the AI does all the implementation, how do junior engineers learn? The intuition of a senior engineer comes from years of wrestling with syntax and low-level bugs. If we bypass that struggle, we may be raising a generation of "architects" who don't understand the bricks they are building with. This could lead to a fragility in the workforce where no one knows how to fix the machine when the autopilot disengages.

3. Hallucinated Dependencies and Security

AI agents have been known to hallucinate dependencies or use insecure patterns if not strictly guardrailed . In a 100% AI model, the review process becomes the only line of defense. If the human reviewer becomes complacent—trusting the "green checkmark" of the agent—security vulnerabilities can slip through at scale.

Conclusion: The Architect's New Role

The transition to AI-native engineering is not about replacing engineers; it is about elevating them. The role shifts from "laborer" to "foreman."

The engineers who thrive in this new era will not be the ones who can type the fastest or memorize the most standard library functions. They will be the ones who can think most clearly, who can decompose complex problems into discrete plans, and who can rigorously assess the quality of an output they didn't produce.

We are moving from an era of writing software to an era of managing software creation. The 10x difference lies not just in the tools, but in the mindset: accepting that the code itself is transient, but the process of generating it is the true asset.

I take on a small number of AI insights projects (think product or market research) each quarter. If you are working on something meaningful, lets talk. Subscribe or comment if this added value.

Appendices

Glossary

- Compounding Engineering: A software development methodology where every unit of work includes a 'codification' step (updating prompts/context) to make subsequent work easier.

- Context File: A persistent document (e.g.,

CLAUDE.mdorRULES.md) that stores architectural decisions, coding standards, and lessons learned for AI agents to reference. - Fractured Attention: The ability to perform complex technical work in short, interrupted bursts because an AI agent maintains the necessary working memory/context.

Contrarian Views

- The Maintenance Nightmare: Critics argue that 100% AI-generated code will eventually become a 'black box' that no human can debug, leading to a catastrophic 'maintenance cliff' when the AI fails.

- Skill Atrophy: If junior engineers never struggle with low-level implementation, they may never develop the intuition required to be effective senior architects.

- Cost of Compute: While human labor costs drop, the inference costs (API fees) for running dozens of agents in parallel can be significant, potentially offsetting savings.

Limitations

- Scale: The 'one engineer, one product' model is proven for small-to-medium SaaS apps but may break down for massive, distributed systems (e.g., Google Search, Netflix infrastructure).

- Determinism: AI agents are non-deterministic; they may solve the same problem differently twice, leading to inconsistent code patterns if not strictly managed.

Further Reading

- Agentic Patterns: Compounding Engineering - https://agentic-patterns.com/patterns/compounding-engineering

- The Impact of AI on Software Engineering Roles (LinearB) - https://linearb.io/blog/agentic-ai-software-engineering

References

- The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity: Evidence from GitHub Copilot - arXiv (journal, 2023-02-13) https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.06590 -> Supports the baseline claim of productivity gains in 'AI-assisted' workflows.

- The AI-native startup: 5 products, 7-figure revenue, 100% AI-written code - Dan Shipper / Every (video, 2025-07-17) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=example-url -> Primary source for the '100% AI' and 'Compounding Engineering' concepts.

- Maker's Schedule, Manager's Schedule - Paul Graham (org, 2009-07-01) http://www.paulgraham.com/makersschedule.html -> Foundational concept used to contrast with the new 'Fractured Attention' capability.

- Dangers of AI-Generated Code: Less Is More - Startup Hakk (news, 2025-05-27) https://startuphakk.com/dangers-of-ai-generated-code-less-is-more/ -> Provides the counter-argument regarding 'digital pollution' and code bloat.

- The Hidden Risks of AI Code Generation - Flux (whitepaper, 2025-06-17) https://askflux.ai/risks-of-ai-code-generation -> Highlights security risks and 'hallucinated dependencies' in AI code.

- Compounding Engineering Pattern - Agentic Patterns (documentation, 2025-12-01) https://agentic-patterns.com/patterns/compounding-engineering -> Defines the specific technical steps of the compounding engineering loop.

- The impact of agentic AI on software engineering roles - LinearB (org, 2025-06-25) https://linearb.io/blog/agentic-ai-software-engineering -> Corroborates the shift from 'coder' to 'architect' or 'orchestrator'.

- Intercom's playbook for becoming an AI-native business - Bessemer Venture Partners (org, 2025-07-21) https://www.bvp.com/atlas/intercoms-playbook-for-becoming-an-ai-native-business -> Shows broader industry movement toward AI-native structures beyond just the primary example.

- Why AI-Generated Code Costs More to Maintain - AlterSquare (news, 2025-11-05) https://altersquare.io/ai-code-maintenance-costs -> Discusses the long-term maintenance costs that balance out the short-term speed.

- Generative AI and the Future of Work in America - McKinsey Global Institute (whitepaper, 2023-07-26) https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/generative-ai-and-the-future-of-work-in-america -> Broad economic context on the shift in knowledge work automation.

Recommended Resources

- Signal and Intent: A publication that decodes the timeless human intent behind today's technological signal.

- Thesis Strategies: Strategic research excellence — delivering consulting-grade qualitative synthesis for M&A and due diligence at AI speed.

- Blue Lens Research: AI-powered patient research platform for healthcare, ensuring compliance and deep, actionable insights.

- Outcomes Atlas: Your Atlas to Outcomes — mapping impact and gathering beneficiary feedback for nonprofits to scale without adding staff.

- Qualz.ai: Transforming qualitative research with an AI co-pilot designed to streamline data collection and analysis.